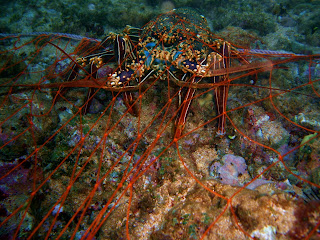

The spiny lobster ('ula in Hawaiian) was given its name because of the spines pointing forward on its carapace (thick, hard shell) and antennae. Readers of this blog who are more familiar with the huge-clawed Maine lobster will note that the spiny lobster lacks this formidable appendage.

Because of disregard for local laws and heavy fishing pressure, large spiny lobsters are no longer common. To protect the species, harvesting is prohibited during the months of May to August. Bruddah Charlie, my go-to guy for fishing Hawaiiana, shared with me that the local way to remember when one can legally catch lobsters is to fish for them only in the months that have the letter R.

Spawning is an interesting process. The male spiny lobster--stimulated by the female's pheromones--attaches a packet of sperm to the area near her reproductive opening. A female spiny lobster produces up to a half million orange or reddish-colored eggs. As the eggs leave her body, they become fertilized. The resulting egg mass is held under her abdomen by unique appendages called swimmerets. These swimmerets are also used to fan and aerate the growing embryos.

Female lobsters carrying eggs are called berried females. It is against the law in Hawaii to capture egg-carrying female lobsters.

Although the eggs will hatch in only a month's time, it will be almost a year before the widely scattered larvae begin to look like lobsters.

There are two main methods of catching lobsters in Hawaii. One way is to dive for and grab them by hand. Lobsters live on the reef or in protected shelves exposed to surge.

One can also set lobster nets. As a young boy, I remember with great fondness my father taking my brothers and me down to the beach. His targeted spots were areas that were shallow and only a few yards away from shore. He would find an open channel--a sandy area with minimal wave action--and secure each end of the net to the rocks bordering each side of the channel. As I recall (and this is going back fifty years, dear readers), the length of each net was approximately 60 feet. I remember this because this is the distance between each base in Little League baseball.

Lobster nets were set in the late afternoon. My father used both heavy rocks and metal hooks to anchor the nets.

Early the next morning, we would pull the nets in. In the late '50's and '60's, we would average a harvest of forty to fifty pounds using three to five nets. Enough to feed our family for a few days and sell to others for some side money.

The net itself was usually only 4 feet tall. Lead weights at the bottom; wood floats on top. To save money, my father smelted his own lead, using scrap metal he had found on the island. Case in point: the remnants of a movie theater that had been demolished in a hurricane. He cut down hau bush* saplings and cut them to four-inch lengths and drilled holes down their core to construct floats. (I have personally observed my father using an electric drill, approaching the core from both ends of the float, but Bruddah Charlie told me recently that he witnessed our father using a red hot metal rod to create the hole for the rope to pass through each float.) Both lead and floats were spaced equidistantly about a yard apart along the length of the net. The eye of a lobster net was larger than the eye of a fishnet. Each eye, diagonally measured, was approximately four inches.

*http://www.canoeplants.com/hau.html copyright 1994 - 2005 by Lynton Dove White

My father sewed his own nets. With string, thin rope, and bamboo sewing needles purchased from a local fishing supply store, and using a measuring rectangular device made from either wood or metal, he would diligently work on each net following a long day at his regular job as a sugar plantation laborer (and, later, as a police officer).

As a young boy, I marveled to see how my father patiently crafted the net from a skein of string to the finished product--a strong and well-crafted lobster net--in just a few days. My best recollection is that he had approximately a dozen of these nets. He would rotate the usage of these nets depending on how many needed to be patched because of holes created by normal wear and tear, sharp reefs, crabs, and--I dared wonder--maybe even sharks?

On a recent evening when the Kauai sky was brilliantly illuminated by a full moon, Bruddah Charlie added to my admittedly limited knowledge about lobsters. He said that lobsters are reluctant to crawl when it is too light outside. They prefer foraging for food in the darkness. So the best time to set lobster nets is when the moon is small.

And what do lobsters eat? Like many people, I thought lobsters were scavengers, eating only dead fish or scraps from another predator's dining. In my research, I learned otherwise. Lobsters actually enjoy the fresh seafood that coexist in close proximity to them. They enjoy fish, mussels, clams, oysters, crabs, and--yes!--other lobsters! Lobsters just love other lobsters...apparently, in more ways than one.

Because of disregard for local laws and heavy fishing pressure, large spiny lobsters are no longer common. To protect the species, harvesting is prohibited during the months of May to August. Bruddah Charlie, my go-to guy for fishing Hawaiiana, shared with me that the local way to remember when one can legally catch lobsters is to fish for them only in the months that have the letter R.

|

| Photo courtesy of Silas Kaumakahia Aqui |

Female lobsters carrying eggs are called berried females. It is against the law in Hawaii to capture egg-carrying female lobsters.

Although the eggs will hatch in only a month's time, it will be almost a year before the widely scattered larvae begin to look like lobsters.

There are two main methods of catching lobsters in Hawaii. One way is to dive for and grab them by hand. Lobsters live on the reef or in protected shelves exposed to surge.

One can also set lobster nets. As a young boy, I remember with great fondness my father taking my brothers and me down to the beach. His targeted spots were areas that were shallow and only a few yards away from shore. He would find an open channel--a sandy area with minimal wave action--and secure each end of the net to the rocks bordering each side of the channel. As I recall (and this is going back fifty years, dear readers), the length of each net was approximately 60 feet. I remember this because this is the distance between each base in Little League baseball.

Lobster nets were set in the late afternoon. My father used both heavy rocks and metal hooks to anchor the nets.

Early the next morning, we would pull the nets in. In the late '50's and '60's, we would average a harvest of forty to fifty pounds using three to five nets. Enough to feed our family for a few days and sell to others for some side money.

|

| Photo courtesy of Silas Kaumakahia Aqui |

*http://www.canoeplants.com/hau.html copyright 1994 - 2005 by Lynton Dove White

My father sewed his own nets. With string, thin rope, and bamboo sewing needles purchased from a local fishing supply store, and using a measuring rectangular device made from either wood or metal, he would diligently work on each net following a long day at his regular job as a sugar plantation laborer (and, later, as a police officer).

As a young boy, I marveled to see how my father patiently crafted the net from a skein of string to the finished product--a strong and well-crafted lobster net--in just a few days. My best recollection is that he had approximately a dozen of these nets. He would rotate the usage of these nets depending on how many needed to be patched because of holes created by normal wear and tear, sharp reefs, crabs, and--I dared wonder--maybe even sharks?

On a recent evening when the Kauai sky was brilliantly illuminated by a full moon, Bruddah Charlie added to my admittedly limited knowledge about lobsters. He said that lobsters are reluctant to crawl when it is too light outside. They prefer foraging for food in the darkness. So the best time to set lobster nets is when the moon is small.

|

| Photo courtesy of Silas Kaumakahia Aqui |

No comments:

Post a Comment